Stanford’s Optical Cavity Arrays Offer a Path Toward Million-Qubit Quantum Systems

Insider Brief

- Researchers led by Stanford University demonstrated scalable optical cavity arrays that enable fast, parallel readout of atom-based qubits, addressing a key bottleneck in building large-scale quantum computers.

- The study, published in Nature, reports a working 40-cavity atom-qubit array and a prototype exceeding 500 cavities, showing a path toward networking millions of qubits.

- By equipping each atom with its own optical cavity to efficiently collect emitted photons, the approach supports future quantum data centers and could accelerate applications ranging from materials and drug discovery to sensing and astronomy.

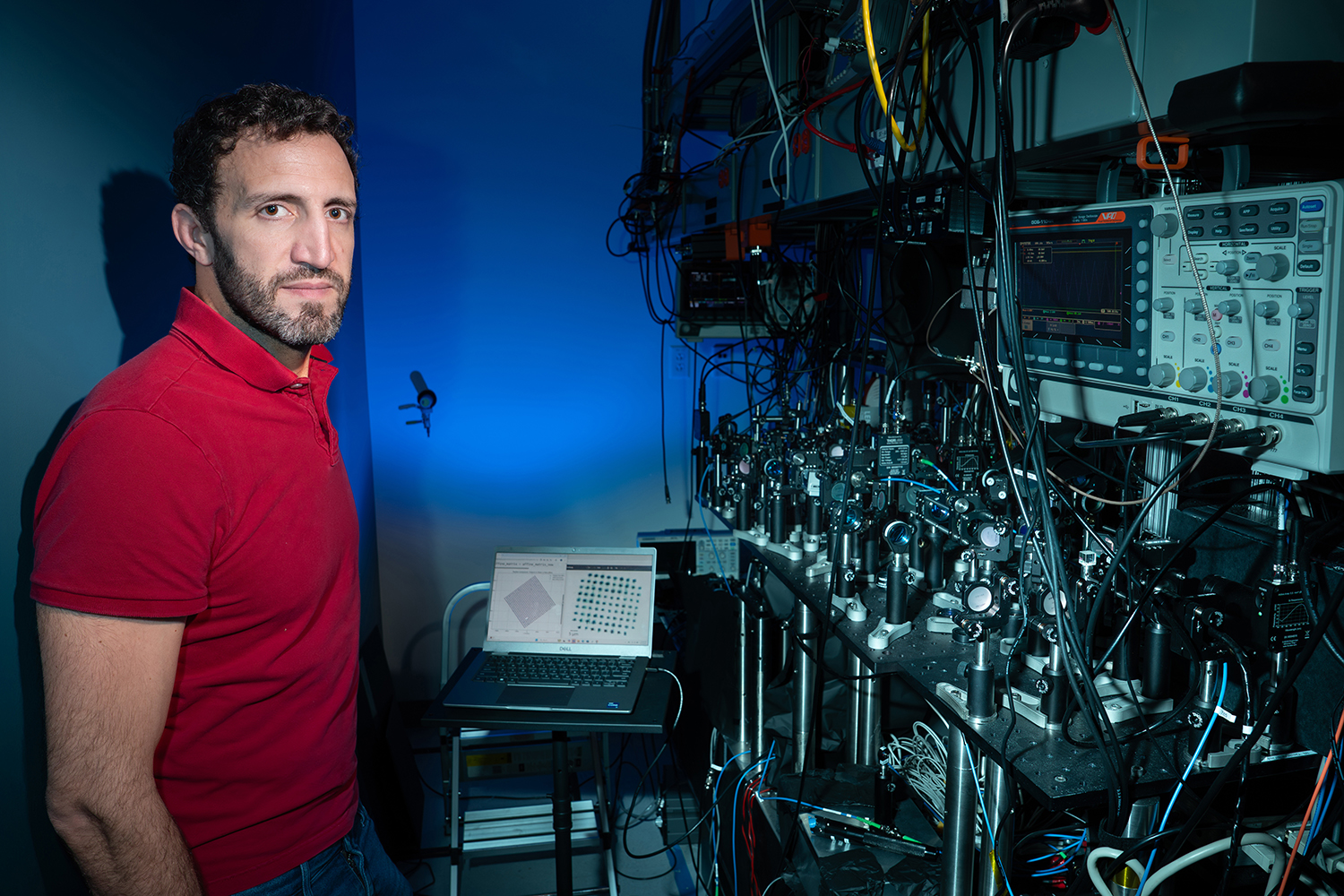

- Story: Stanford Report. Image: LiPo Ching for Stanford University

PRESS RELEASE — A light has emerged at the end of the tunnel in the long pursuit of developing quantum computers, which are expected to radically reduce the time needed to perform some complex calculations from thousands of years down to a matter of hours.

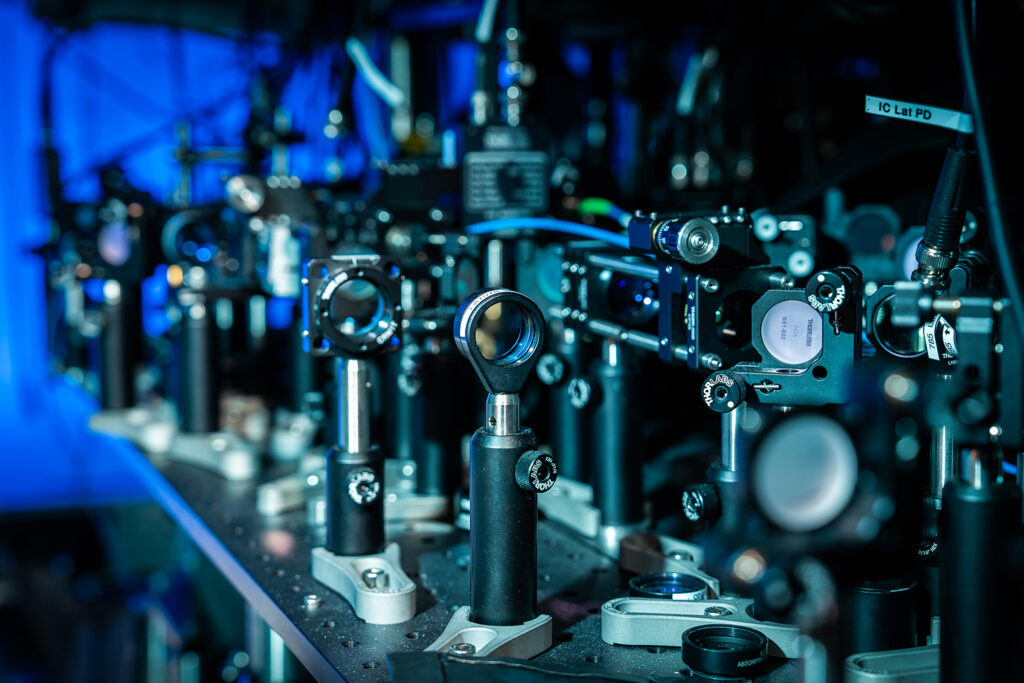

A team led by Stanford physicists has developed a new type of “optical cavity” that can efficiently collect single photons, the fundamental particle of light, from single atoms. These atoms act as the building blocks of a quantum computer by storing “qubits” – the quantum version of a normal computer’s bits of zeros and ones. This work enables that process for all qubits simultaneously, for the first time.

In a study published in Nature, the researchers describe an array of 40 cavities containing 40 individual atom qubits as well as a prototype with more than 500 cavities. The findings indicate a way to ultimately create a million-qubit quantum computer network.

“If we want to make a quantum computer, we need to be able to read information out of the quantum bits very quickly,” said Jon Simon, the study’s senior author and the Joan Reinhart Professor in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences. “Until now, there hasn’t been a practical way to do that at scale because atoms just don’t emit light fast enough, and on top of that, they spew it out in all directions. An optical cavity can efficiently guide emitted light toward a particular direction, and now we’ve found a way to equip each atom in a quantum computer within its own individual cavity.”

A light has emerged at the end of the tunnel in the long pursuit of developing quantum computers, which are expected to radically reduce the time needed to perform some complex calculations from thousands of years down to a matter of hours.

A team led by Stanford physicists has developed a new type of “optical cavity” that can efficiently collect single photons, the fundamental particle of light, from single atoms. These atoms act as the building blocks of a quantum computer by storing “qubits” – the quantum version of a normal computer’s bits of zeros and ones. This work enables that process for all qubits simultaneously, for the first time.

In a study published in Nature, the researchers describe an array of 40 cavities containing 40 individual atom qubits as well as a prototype with more than 500 cavities. The findings indicate a way to ultimately create a million-qubit quantum computer network.

“If we want to make a quantum computer, we need to be able to read information out of the quantum bits very quickly,” said Jon Simon, the study’s senior author and the Joan Reinhart Professor in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences. “Until now, there hasn’t been a practical way to do that at scale because atoms just don’t emit light fast enough, and on top of that, they spew it out in all directions. An optical cavity can efficiently guide emitted light toward a particular direction, and now we’ve found a way to equip each atom in a quantum computer within its own individual cavity.”

Researchers estimate a quantum computer will require millions of qubits to outperform classical supercomputers. Reaching that number will likely mean networking many quantum computers together, Simon said. The achievement in this study of using cavities to create a parallel interface makes a highly efficient platform for scaling to these large sizes.

The team demonstrated a 40-cavity array containing atoms in this paper with a proof-of-concept array with more than 500, and the researchers are aiming toward tens of thousands. Looking ahead, they imagine quantum data centers where individual quantum computers each have a network interface consisting of a cavity array, enabling large-scale integration into quantum supercomputers.

Reaching that goal will require solving some major engineering challenges, but the potential is there, the researchers contend, and with it, all the promise of quantum computing. This could mean major advances in materials design and chemical synthesis, such as that used for drug discovery, as well as in code breaking. More broadly, the light-collection capabilities of the cavity arrays hold great promise for biosensing and microscopy, which could advance medical and biological research. Quantum networks could even help better understand space, by enabling optical telescopes with enhanced resolution that would allow direct observation of planets outside our solar system.

“As we understand more about how to manipulate light at a single particle level, I think it will transform our ability to see the world,” Shaw said.

Simon is a professor of physics and of applied physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences. Shaw is also a Felix Bloch Fellow and an Urbanek-Chodorow Fellow.

Additional Stanford co-authors include David Schuster, the Joan Reinhart Professor and professor of applied physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences, and doctoral students Anna Soper, Danial Shadmany, and Da-Yeon Koh.

Other co-authors include researchers from Stony Brook University, the University of Chicago, Harvard University, and Montana State University.

This research received support from the National Science Foundation, Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Army Research Office, Hertz Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Defense.

Matt Jaffe of Montana State University and Simon act as consultants to and hold stock options in Atom Computing. Shadmany, Jaffe, Schuster, and Simon, as well as Aishwarya Kumar of Stony Brook, hold a patent on the resonator geometry demonstrated in this work.