Scientists Capture a Glimpse Into The Quantum Vacuum

Insider Brief

- Scientists at the Brookhaven National Laboratory report experimental evidence that particles produced in high-energy collisions retain spin correlations originating from entangled virtual quark–antiquark pairs in the quantum vacuum, offering a new way to study how visible matter emerges from vacuum fluctuations.

- Using data from the STAR Collaboration at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider, the study found that lambda and antilambda particles produced close together in proton-proton collisions are fully spin aligned, directly linking their properties to spin-aligned virtual strange quark pairs in the vacuum.

- Published in Nature, the results provide a new experimental handle on the quantum-to-classical transition in matter formation, with implications for nuclear physics, quantum information science, and future experiments at RHIC and the planned Electron-Ion Collider.

PRESS RELEASE — Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory have uncovered experimental evidence that particles of matter emerging from energetic subatomic smashups retain a key feature of virtual particles that exist only fleetingly in the quantum vacuum. The finding offers a new way to explore how the vacuum — once thought of as empty space — provides important ingredients needed to transform virtual “nothingness” into the matter that makes up our world.

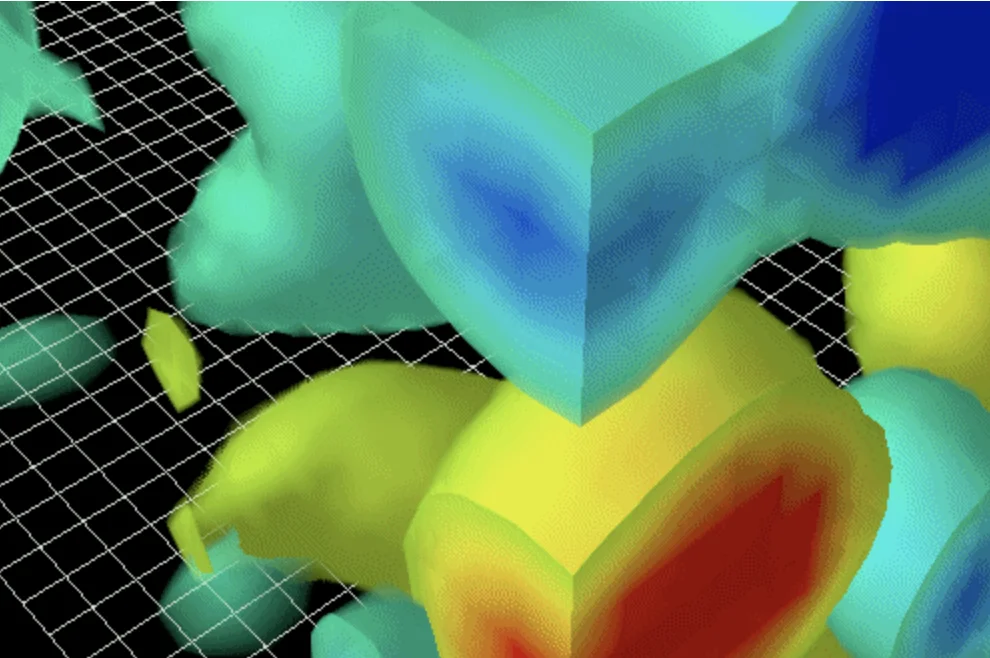

The research, just published in Nature, was carried out by the STAR Collaboration at Brookhaven’s Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), a DOE Office of Science user facility for nuclear physics research. The Nature paper presents evidence of a significant correlation in particle spins — a built-in quantum property related to magnetism — among certain pairs of particles emerging from proton-proton collisions at RHIC. The STAR scientists’ analysis directly links those correlations to the spin alignment of virtual quark-antiquark pairs generated in the quantum vacuum. In essence, the scientists say, RHIC’s collisions give those virtual particles the energetic boost they need to transform into the real particles detected by STAR.

“This work gives us a unique window into the quantum vacuum that may open a new era in our understanding of how visible matter forms and how its fundamental properties emerge,” said Zhoudunming (Kong) Tu, a STAR physicist at Brookhaven and co-leader of the study.

From entangled vacuum to visible matter

In reality, as physicists have known for about 100 years, the vacuum is anything but empty. It’s filled with fluctuating energy fields that can briefly create entangled pairs of particles and their opposites, called antiparticles. These “virtual” and inherently linked matter-antimatter pairs blink in and out of existence on very short timescales but never stick around long enough to be counted as “real.” In RHIC’s energetic proton-proton collisions, however, some of those pairs gain enough energy to become real components of detectable particles.

In the new study, physicists searched for so-called lambda hyperons and their antimatter counterparts, antilambdas. They wanted to see if and how much these particles’ spins were aligned as they emerged from collisions at RHIC.

Lambdas are ideal for studying spin because the direction of a lambda’s spin can be inferred from the direction in which a proton or antiproton is produced as these particles decay. Lambdas also each have a component that the STAR physicists say allows them to retrace its origins — a so-called strange quark, or a strange antiquark in the case of the antilambda. Strange quark/antiquark pairs generated as virtual particles in the vacuum are always spin aligned, whereas most of the particles generated in RHIC collisions have no set spin direction. If the spins of lambda and antilambda particles emitted together from collisions are aligned, it would be strong evidence that these particles have a connection to a spin-aligned virtual strange quark pair in the vacuum.

Searching for spin alignments

“Normally, in a RHIC collision, the spins of the vast majority of particles that come out are randomly oriented. We are looking for a very tiny difference from all those other particles to find lambda/antilambdas where their spins are correlated,” said Jan Vanek, a physicist at the University of New Hampshire who led the data analysis while a postdoctoral researcher at Brookhaven.

The STAR team examined data from millions of proton-proton collision events, carefully eliminating any biases and sources of false signals. This analysis revealed that when lambdas and antilambdas emerge from a collision close together, they are 100% spin aligned — just like the virtual quark/antiquark pairs in the vacuum. This provides strong evidence that the strange/antistrange quarks in the two separate lambda particles originated as a single entangled quark/antiquark pair. In other words, the quarks in the two separate particles retained a spin linkage that was established in the quantum vacuum before the lambda particles formed.

As Vanek noted, “It’s as if these particle pairs start out as quantum twins. When they’re generated close together, the lambdas retain the spin alignment of the virtual strange quarks from which they were born.”

A quantum connection

“This is the first time we’ve been able to see directly that the quarks that make up these particles are coming from the vacuum; it’s a direct window into the quantum vacuum fluctuations,” Tu said. “It’s amazing to see that the spin alignment of the entangled virtual quarks survives the process of transformation into real matter.”

The researchers say that this quantum linkage may hint at a deeper entanglement between the newly formed lambda/antilambda pair, in which the properties of two particles remain connected even when they’re separated. However, when the STAR physicists looked at lambda/antilambda pairs emerging farther apart in RHIC collisions, these real particles were no longer spin correlated.

“It could be that these twins sent farther away from each other are more affected by other things in their environment — interactions with other quarks, for example — that cause them to behave differently and lose their connection,” Vanek said. “We need further measurements to see if this is a mix of entangled states or a more classically correlated system.”

Either way, the connection between the entangled quarks within the quantum vacuum and ordinary particles detected at RHIC could give scientists a way to explore the transition from quantum to classical states of matter. That’s an important area of research that’s relevant to quantum information science and quantum-based technologies.

“The problem, at its core, could impact other parallel technology developments that require us to study this quantum to classical transition because, at the end of the day, the physics is the same,” Tu said.

Links to mass and big mysteries

Understanding how quarks transition from free-moving entities into bound particles like protons, neutrons, and hyperons is one of the central challenges of nuclear physics. The new approach opens a path to explore key questions that underlie how mass and structure emerge in the universe.

“In our experiment, the energy needed to transform virtual particles from the vacuum into real matter comes from the RHIC collisions,” Tu said. “Now we can reverse engineer it to explore this complicated process.”

For example, Tu explained that the connection between the lambda decays and the strange quark spins in the vacuum could be used to study how matter is formed in atomic nuclei — a much more complicated system than simple protons, neutrons, or even hyperons.

“Just like the quantum twins, we can send virtual quark-antiquark pairs through different ‘environments,’ or types of nuclei, to see how they ‘grow up’ — and study how their connectedness shows up in their ‘adult’ lives,” he said.

This approach can be extended to the collisions of nuclei at RHIC and also collisions at the future Electron-Ion Collider (EIC) — a nuclear physics research facility to be built at Brookhaven by reusing much of the infrastructure at RHIC. The EIC will provide even sharper tools to explore the connection between the vacuum and the mass of our visible universe, from the smallest subatomic components to stars, planets, galaxies, and even people.

On a larger scale, the study advances scientists’ understanding about one of the biggest mysteries of humankind: “how something — the visible matter of our universe — connects to the ‘nothingness’ of the vacuum,” Tu said.

This work was supported by the DOE Office of Science, the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), and a range of international agencies and organizations listed in the scientific paper. In addition to using the Open Science Grid, supported directly by NSF, the researchers made use of computing resources in the Scientific Data and Computing Facilities at Brookhaven Lab and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), which is another DOE Office of Science user facility at DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.