Researchers Demonstrate Fault-Tolerant Quantum Operations Using Lattice Surgery

Insider Brief

- Researchers demonstrated lattice surgery on superconducting qubits, enabling a fault-tolerant quantum operation between logical qubits while correcting errors during the operation.

- The experiment used surface-code error correction to split a single logical qubit encoded in 17 physical qubits into two entangled logical qubits, addressing constraints of fixed, two-dimensional qubit layouts.

- While not yet fully robust against all error types and requiring more physical qubits for scalability, the work represents a concrete step toward practical, large-scale quantum computers.

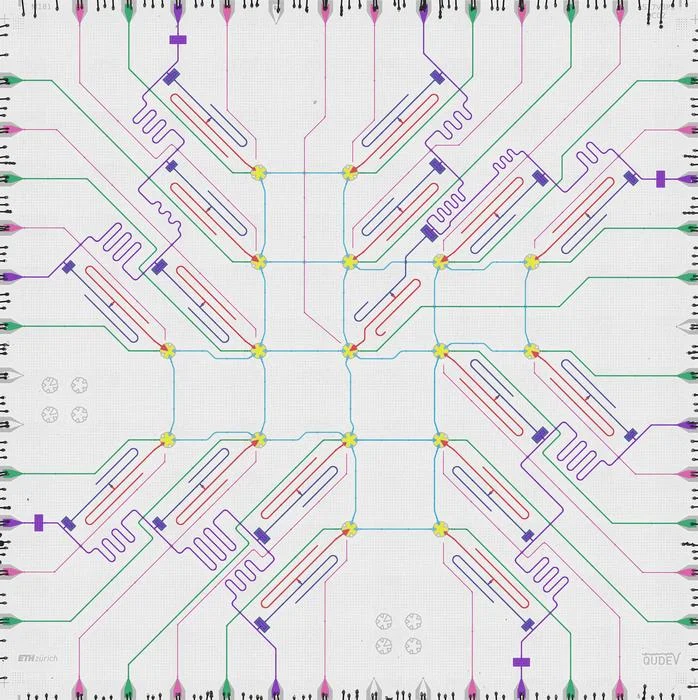

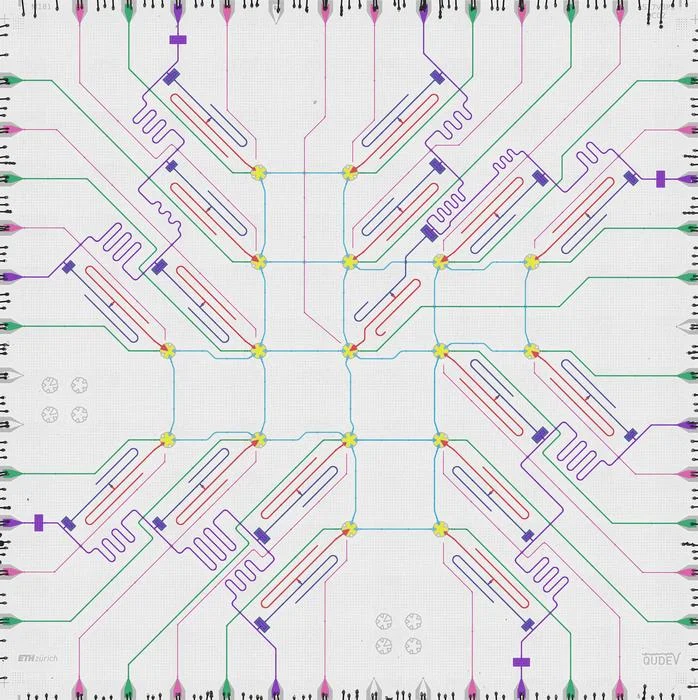

- Image: False-coloured optical photo of the quantum chip used in the experiment. (Quantum Device Lab / ETH Zurich)

PRESS RELEASE — Quantum computers hold great promise for exciting applications in the future, but for now they keep presenting physicists and engineers with a series of challenges and conundrums. One of them relates to decoherence and the errors that result from it: bit flips and phase flips. Such errors mean that the logical unit of a quantum computer, the qubit, can suddenly and unpredictably change its state from ‘0’ to ‘1’, or that the relative phase of a superposition state can jump from positive to negative.

These errors can be held at bay by building a logical qubit out of many physical qubits and constantly applying error correction protocols. This approach takes care of storing the quantum information relatively safely over time. However, at some point it becomes necessary to exit storage mode and do something useful with the qubit – like applying a quantum gate, which is the building block of quantum algorithms.

The research group led by D-PHYS Professor Andreas Wallraff, in collaboration with the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) and the theory team of Professor Markus Müller at RWTH Aachen University and Forschungszentrum Jülich, has now demonstrated a technique that makes it possible to perform a quantum operation between superconducting logical qubits while correcting for potential errors occurring during the operation. The researchers have just published their results in Nature Physics.

Quantum error correction is very different from classical error correction. For the latter, it’s possible to make several identical copies of a bit and read them out after a while: if a bit flip occurred, a majority vote reveals which bit most likely flipped and its original value can be restored. “With qubits, things are a lot more complicated,” says Dr Ilya Besedin, postdoctoral researcher in Wallraff’s group and co-leading author of the study together with PhD student Michael Kerschbaum. One complication is that quantum information cannot simply be copied or ‘cloned’: instead, one must create entangled states of several qubits. To make things even trickier, phase-flip errors – which do not exist in classical computation – also need to be fixed.

Error correction with surface codes

One way to ensure that bit- and phase-flip errors are corrected is to use so-called surface codes. In these codes, the state of a qubit is stored in several physical data qubits. Error correction is achieved by measuring repeatedly the quantum states of so-called stabilizers, which make up the logical qubit together with data qubits. Stabilizers are measured using extra qubits that are connected to data qubits in such a way that reading them out reveals any changes – in bit value (Z-type stabilizer) or phase (X-type stabilizer) – occurring between measurements, thus enabling their correction. Data qubits, on the other hand, are never read out: they store the error-corrected qubit state.

The situation changes when one wants to perform a quantum logical operation, such as a controlled-NOT gate, between two logical qubits. In particular, one must also correct for any errors occurring during the operation. “Performing a logical operation in this fault-tolerant way would be relatively easy if we could move our qubits around and connect them arbitrarily to each other,” says Kerschbaum. In two-dimensional arrays of superconducting qubits, however, each qubit is fixed in space, and only physical qubits that are spatially close to each other are connected and can interact with one another.

Splitting the square

“Lattice surgery is a way of dealing with this constraint,” says Kerschbaum. In their experiment, he and his colleagues initially performed error correction on a single logical qubit that was encoded by seventeen physical qubits. The data qubits and the stabilizers were arranged in a roughly square shape. For a few cycles, the researchers read out the stabilizers every 1.66 microseconds, performing bit-flip and phase-flip error correction.

When the time for surgery came, three data qubits along the middle of the square were read out, effectively splitting the surface-code square into two halves. Additionally, the readout of the X-type stabilizers was halted. “The end result of this operation was that we had two logical qubits entangled with each other,” explains Besedin. During the surgery, bit-flip errors were corrected; afterwards, bit-flip error correction could continue on the two resulting halves. This operation isn’t yet a quantum controlled-NOT gate, but it can be turned into one through a series of such splits together with merging operations.

Quantum computers hold great promise for exciting applications in the future, but for now they keep presenting physicists and engineers with a series of challenges and conundrums. One of them relates to decoherence and the errors that result from it: bit flips and phase flips. Such errors mean that the logical unit of a quantum computer, the qubit, can suddenly and unpredictably change its state from ‘0’ to ‘1’, or that the relative phase of a superposition state can jump from positive to negative.

These errors can be held at bay by building a logical qubit out of many physical qubits and constantly applying error correction protocols. This approach takes care of storing the quantum information relatively safely over time. However, at some point it becomes necessary to exit storage mode and do something useful with the qubit – like applying a quantum gate, which is the building block of quantum algorithms.

The research group led by D-PHYS Professor Andreas Wallraff, in collaboration with the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) and the theory team of Professor Markus Müller at RWTH Aachen University and Forschungszentrum Jülich, has now demonstrated a technique that makes it possible to perform a quantum operation between superconducting logical qubits while correcting for potential errors occurring during the operation. The researchers have just published their results in Nature Physics.

Quantum error correction is very different from classical error correction. For the latter, it’s possible to make several identical copies of a bit and read them out after a while: if a bit flip occurred, a majority vote reveals which bit most likely flipped and its original value can be restored. “With qubits, things are a lot more complicated,” says Dr Ilya Besedin, postdoctoral researcher in Wallraff’s group and co-leading author of the study together with PhD student Michael Kerschbaum. One complication is that quantum information cannot simply be copied or ‘cloned’: instead, one must create entangled states of several qubits. To make things even trickier, phase-flip errors – which do not exist in classical computation – also need to be fixed.

Error correction with surface codes

One way to ensure that bit- and phase-flip errors are corrected is to use so-called surface codes. In these codes, the state of a qubit is stored in several physical data qubits. Error correction is achieved by measuring repeatedly the quantum states of so-called stabilizers, which make up the logical qubit together with data qubits. Stabilizers are measured using extra qubits that are connected to data qubits in such a way that reading them out reveals any changes – in bit value (Z-type stabilizer) or phase (X-type stabilizer) – occurring between measurements, thus enabling their correction. Data qubits, on the other hand, are never read out: they store the error-corrected qubit state.

The situation changes when one wants to perform a quantum logical operation, such as a controlled-NOT gate, between two logical qubits. In particular, one must also correct for any errors occurring during the operation. “Performing a logical operation in this fault-tolerant way would be relatively easy if we could move our qubits around and connect them arbitrarily to each other,” says Kerschbaum. In two-dimensional arrays of superconducting qubits, however, each qubit is fixed in space, and only physical qubits that are spatially close to each other are connected and can interact with one another.

Splitting the square

“Lattice surgery is a way of dealing with this constraint,” says Kerschbaum. In their experiment, he and his colleagues initially performed error correction on a single logical qubit that was encoded by seventeen physical qubits. The data qubits and the stabilizers were arranged in a roughly square shape. For a few cycles, the researchers read out the stabilizers every 1.66 microseconds, performing bit-flip and phase-flip error correction.

When the time for surgery came, three data qubits along the middle of the square were read out, effectively splitting the surface-code square into two halves. Additionally, the readout of the X-type stabilizers was halted. “The end result of this operation was that we had two logical qubits entangled with each other,” explains Besedin. During the surgery, bit-flip errors were corrected; afterwards, bit-flip error correction could continue on the two resulting halves. This operation isn’t yet a quantum controlled-NOT gate, but it can be turned into one through a series of such splits together with merging operations.

“One could say that the lattice surgery operation is the operation, and all the others can be constructed from it,” says Besedin. “To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time lattice surgery has been performed on superconducting qubits,” he adds, “and we still have some way to go.

For instance, 41 physical qubits would be required to make the splitting operation on one logical qubit stable against phase flips too. Nonetheless, this demonstration of lattice surgery on superconducting qubits marks an important step towards the ambitious goal of building useful quantum computers with thousands of qubits.

“One could say that the lattice surgery operation is the operation, and all the others can be constructed from it,” says Besedin. “To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time lattice surgery has been performed on superconducting qubits,” he adds, “and we still have some way to go.

For instance, 41 physical qubits would be required to make the splitting operation on one logical qubit stable against phase flips too. Nonetheless, this demonstration of lattice surgery on superconducting qubits marks an important step towards the ambitious goal of building useful quantum computers with thousands of qubits.

Reference

Besedin, I., Kerschbaum, M. et al. Realizing lattice surgery on two distance-three repetition codes with superconducting qubits. Nat. Phys. (2026). DOI:10.1038/s41567-025-03090-6