University of Stuttgart Spin-Off Wants to Put Quantum Sensors in The Palm of Your Hand

Insider Brief

- SpinMagIC, a spin-off from the University of Stuttgart that is developing a palm-sized quantum sensor to measure food shelf life, secured two years of funding from Germany’s EXIST research transfer program.

- The device uses a microchip and lightweight 3D-printed magnets to detect free radicals, offering a cost-effective alternative to traditional bulky ESR equipment.

- Beyond food quality, the technology has potential applications in battery monitoring, pharmaceutical testing, and environmental contamination measurement.

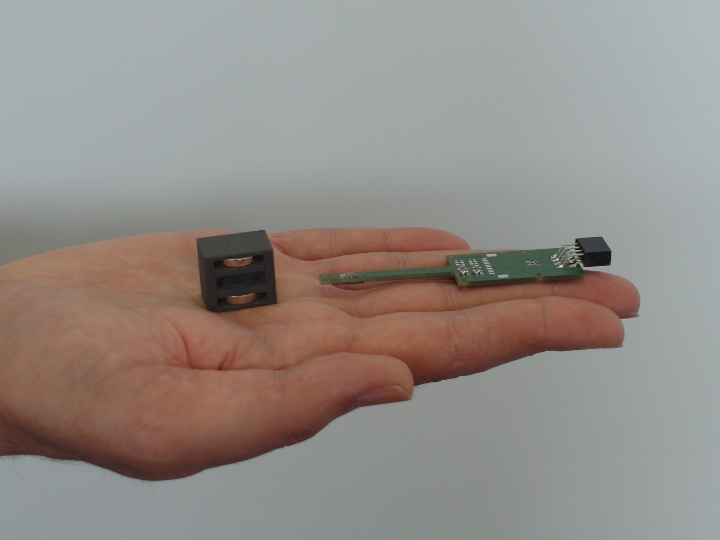

- Image: This is how shelf-life measurement works: On the left, a permanent magnet, alongside a green circuit board, features a tiny chip-integrated quantum sensor. (SpinMagIC)

A spin-off from the University of Stuttgart is aiming to revolutionize how food shelf life and other critical properties are measured using quantum sensors small enough to fit in the palm of a hand, according to a university news release. The startup, SpinMagIC, has secured funding from Germany’s EXIST research transfer program, part of the Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection (BMWK). The funding will provide two years for the team to develop its technology and bring it to market.

Compact Quantum Sensors for Broad Applications

SpinMagIC’s technology leverages electron spin resonance (ESR) to detect free radicals — reactive molecules with unpaired electrons that play a significant role in food decomposition and other chemical processes. Traditional ESR devices have been massive, weighing over a ton and costing hundreds of thousands of euros, limiting their widespread adoption.

“This quantum sensor technology is already just around the corner. Now we need to launch it on the market with full momentum,” said Prof. Jens Anders, who leads the research team at the University of Stuttgart’s Institute for Smart Sensors, in the release.

The innovation centers on miniaturization. Instead of relying on bulky equipment, the new system uses a microchip no larger than a square millimeter, integrated with high-frequency circuit components. A lightweight magnet, weighing just 40 grams and made using 3D printing, provides the necessary magnetic field. Together, these components offer a portable, cost-effective way to measure free radicals in liquids.

How It Works

The sensor can either be immersed directly into a liquid sample or connected to a micropump that delivers the sample onto the chip. The device then excites the unpaired electrons in the sample and detects their quantum responses, which correlate with the number of free radicals. Results are displayed immediately, offering a simple, fast, and reliable method to assess product quality.

Belal Alnajjar, a physicist on the team, said the lightweight magnets were highly precise. “The rings are selected to ensure that the magnetic field is highly homogeneous,” he said in the release, indicating how the design minimizes weight without compromising functionality.

From Research to Market

The spin-off team includes researchers from Stuttgart and Berlin, combining expertise in engineering, physics, and business, according to the release. In Stuttgart, Anders’ doctoral researchers, Alnajjar and Anh Chu, are focused on developing the core technology, including the magnet and circuit board. In Berlin, doctoral researcher Michele Segantini works on applications, such as assessing olive oil quality, leveraging his connections within the food industry. Jakob Fitschen, the team’s business lead, manages finances and profitability.

The startup’s neologism, SpinMagIC, reflects its core components: “Spin” for electron spins, “Mag” for the magnetic field, and “IC” for the integrated circuit.

“Extremely small, incredibly affordable, and with very high measurement accuracy,” said Chu, describing the device’s alignment with food industry demands.

Broader Potential Beyond Food

While the initial focus is on food shelf life, SpinMagIC’s technology has far-reaching implications. It could be used to measure rechargeable battery conditions, monitor air and water contamination, and improve catalytic processes in chemical manufacturing. Applications in pharmaceuticals are also on the horizon.

“We have a fixed budget from the BMWK for the next two years,” Chu said. “But we are also open to venture capitalists and private investors.”

Although the device is still too large to integrate into wearables like smartwatches, the researchers have long-term plans to make it even more compact. The team is confident that its affordable and precise technology will attract pilot customers within two years.